While it’s obvious that companies are made up of their numbers, less is known about the idiosyncratic factors that make businesses special. We look at some of the stories behind the numbers......

Companies are made up of their financial capital, yet crucially, they are comprised of other forms of intangible capital as well, such as human, intellectual, social and environmental capital. These extra-financial factors are what give great businesses their competitive edge. They could be a company’s relationship with its customers, suppliers and the community, the ability to attract and retain talent or a culture of innovation.

Exhibit 1: Contingent assets aren’t reflected in typical financial metrics

Source: RBC GAM.

A company is more than just its numbers

Such factors are poorly represented by traditional financial reporting but positively affect a company’s business performance (for example, through employee engagement, customer satisfaction, a strong corporate culture and/or R&D effectiveness) which ultimately leads to positive corporate – and share price – performance.

An example is a Swiss pharmaceutical company, with very strong ESG credentials observable throughout its business model. Its chosen field of oncology is an area of expanding scientific knowledge but it is also one with broad social benefits, given the number of lives cancer impacts. By fulfilling patients’ unmet needs, the company is able to deliver a significant improvement to the duration and quality of patients’ lives. It has become a trusted partner for medical practitioners because of the quality of its work, enabling it to collaborate on new areas of research. Management has a strong record of meeting its regulatory obligations and during our research, we noted the supportive employee culture.

The other side of the coin

However, in the same way that a company can borrow against financial capital by taking a loan, it can also borrow against extra-financial providers of capital, for example, from its customers by compromising on services, from its suppliers by not paying them on time or from its community by not paying sufficient taxes.

These contingent liabilities – or potential liabilities – are created when a company chooses to compromise the future in order to flatter short-term results. They might be deferred for a period of time but ultimately cannot be avoided, thus impacting the value of a business and resulting in negative financial consequences for shareholders, when they become realised.

An example of a company which we decided not to invest in was a U.S. ‘energy’ drinks company which has attractive margins and sales growth, but in our opinion, the business model is based upon the sale of sugar-heavy, highly-caffeinated drinks to predominately young customers. For some time there have been major concerns about the negative health effects of highly-sugared drinks, and in early 2018 the company’s main customers in the UK – the supermarkets – agreed to restrict sales to over 16s. The shares have yet to price in these contingent liabilities and have been a rewarding investment for shareholders – so far. Nevertheless, we believe that the contingent liabilities remain even if traditional techniques of financial analysis are blind to them.

The power of active ownership

Through an active ownership and engagement approach with the great companies in which we invest, we seek to ensure that positive change is effected over time, or conversely, that the wonderful contingent assets a company builds, are stewarded and looked after. Changes in ESG-related issues cannot happen overnight due to companies’ needs to respond to both their business environments and stakeholder expectations.

We take every opportunity to meet our companies, discuss management’s strategy and cross reference these against our expectations. We partner with companies to improve their ESG credentials or alert them to the fact that some of the positive steps they are taking are not being recognised by the market, due to poor levels of disclosure.

Exhibit 2: Making a positive difference through active engagement

Source: RBC GAM.

An example of successful engagement was with a U.S. wireless network operator, on a broad range of environmental topics, and in particular, on its science-based targets (targets in line with the goals of the Paris Agreement – limiting global warming to below 2°C above pre-industrial levels and pursuing efforts to limit warming to 1.5°C).

The company has sought to reduce its entire carbon footprint, from its operations through to its supply chain. In 2019, the company worked with the Science-Based Targets Initiative (SBTi) to set two science-based emissions targets:

- Target 1 was to reduce combined absolute Scope 1 and 2 greenhouse gas emissions by 95% by 2025, from a 2016 base year, and

- Target 2 was to reduce Scope 3 greenhouse gas emissions by 15% per customer by 2025, from a 2016 base year.

The company was the first U.S. wireless provider to set science-based targets, and the company not only achieved these goals at the end of 2021, but beat them four years ahead of schedule. In 2021, the company reduced Scope 1 and 2 emissions by 96% compared with 2020, and 97% compared with 2016. It also reduced Scope 3 emissions per customer by 2% compared with 2020, and by 16% compared with 2016.

While these are significant steps towards achieving net zero emissions, we have encouraged a revisal of Scope 3 targets. The company acknowledged the proposition and suggested that new initiatives would be announced for the next year. We will continue to monitor the company’s progress and will continue to engage with management.

These on-going dialogues illustrate our responsibility as active and engaged investors. We want to think and act as owners of businesses and we are not simply a name on a share ledger. We are part of a partnership between management and asset managers, on behalf of the ultimate beneficial owners of the shares, who may be several steps removed but nonetheless have placed their trust in their chosen managers to act as fiduciaries.

In effect, we seek to ‘shape’ a company’s business model by working together with companies. We believe that we make a stronger call for change via active ownership and engagement than divestment. Divestment sends out a strong socio-political message, however it also takes away the ability to affect further change and have a positive impact on society.

That said, there have been occasions when divestment has occurred. We invested with a U.S. teen retailer yet after being invested for a period of time, we became increasingly concerned over the quality of the financial results. In particular, a write-off of newly delivered inventory because it was deemed inconsistent with brand values highlighted potentially weak management controls. This was exacerbated by signs of over-investment when opening in new regions and the adoption of unsustainable pricing structures. Having repeatedly questioned management on these issues, the upcoming expiration of senior management’s generous employment contract provided the catalyst for more detailed discussions. However, we were disappointed that despite our discussions, when the new contract was signed there was no evidence that our concerns had been addressed. We were obliged to reassess our view on management and ESG which ultimately led to our divestment from the company.

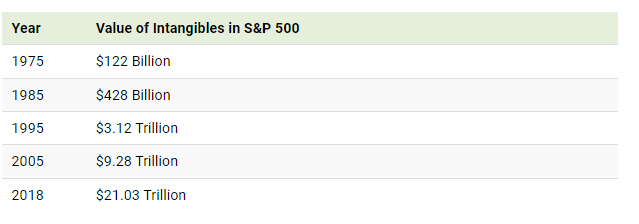

Alpha sources

The world has become much more ‘intangible’ over time, with intangible assets accounting for 90% of S&P 500 Index, compared to just 17% in the 1970s . Much of this capital is difficult to measure and is not well reported on, and we believe that the market often under-appreciates the impact of companies’ extra-financial factors, thereby creating exploitable inefficiencies.

Exhibit 3: The soaring value of intangible assets in the S&P 500 Index

Source: Visualcapitalist.com.

The upside for us, as fundamental active managers, is that our skill and experience in examining these inefficiencies means that we are well placed to seek out differentiated sources of alpha.

We use ESG as a tool to focus on the idiosyncratic aspects of a business that no other company shares, which in turn, helps us to identify intended sources of risk, which is the type of risk that we desire, as bottom-up stock pickers.

We would argue that, for a fundamental, active manager, a portfolio’s risk profiles should dominated by these stock-specific risks, with a minimal level of unintended risk. We are not driven by any kind of investment style. We let our companies tell the stories.

Conclusion

Increasingly, investors care not just about the returns on their investments but how those returns have been generated. They want to know that their capital is not being used to support business activities that do not align with their personal values.

There is no doubt that the numbers are important, however seeking out those companies with strong ESG practices, alongside winning business models, is how we add value. Ultimately, investing in these great businesses should generate long-term value for shareholders that significantly exceeds the return on the average company or the market.

Visit our RBC Global Equity team page to find out who we are, learn more about our team culture and discover how we identify and invest in great businesses.