Malin Rosengren, Investment Grade Portfolio Manager, discusses why a slowdown in US growth risks being exacerbated by limited fiscal space and steep yield curves.

Key takeaways for bond market investors

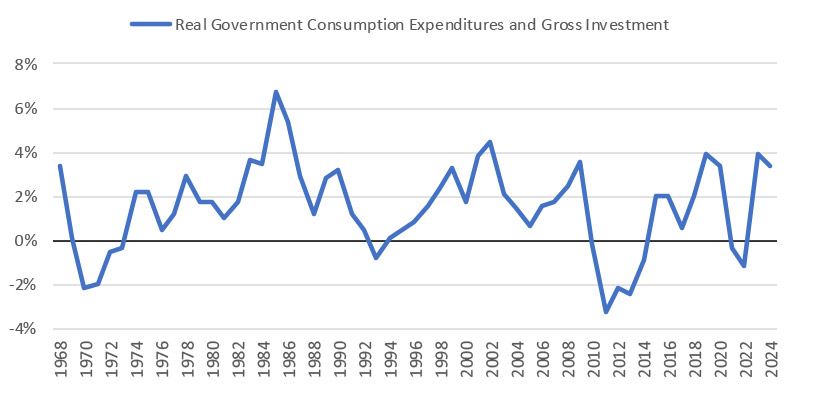

Government contribution to GDP growth can be expected to slow from the average 2% seen over the last decade (Chart 1).

Expect structural steepening pressure to continue, with unabated heavy supply keeping the long end of the curve elevated.

Any slowdown in US growth risks being exacerbated by limited fiscal space and steep yield curves. Fiscal policy anchoring the long end at elevated levels reduces the effectiveness of the Fed’s monetary policy transmission, given the housing market in the US is tied to the long end due to the prominence of 30-year mortgages. Crowding out will bite harder in a downturn.

Chart 1: Real GDP contribution: government consumption and investments

Source: Bloomberg, as at April 2025.

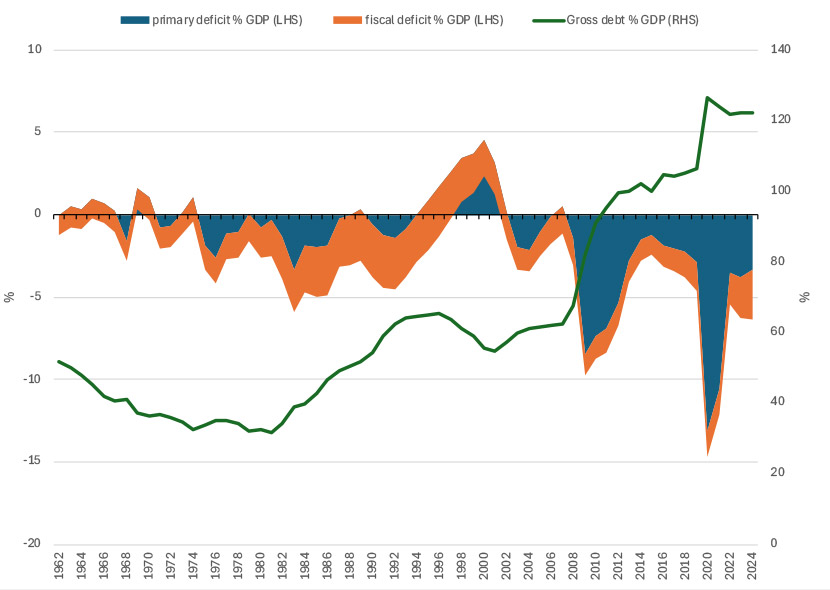

It is no coincidence that US exceptionalism has coincided with the loosest fiscal policy in modern history. Large primary deficits funded by debt accumulation enabled the government to pump fresh demand into the economy – and at little cost. Low yields kept the interest burden contained, helping mask the extent of fiscal expansion.

Since 2010, the US has run a primary budget deficit on average of around -4.5% GDP and accumulated more than 30pp of GDP in additional debt (Chart 2). That’s a solid contribution to growth in the first instance, plus any additional delta from fiscal multipliers depending on the productivity of spending. The larger the growth boost, the greater the ability to spend, the more favourable the debt dynamics.

Chart 2: US exceptionalism defined by the loosest fiscal policy in modern history

Source: Bloomberg, as at April 2025.

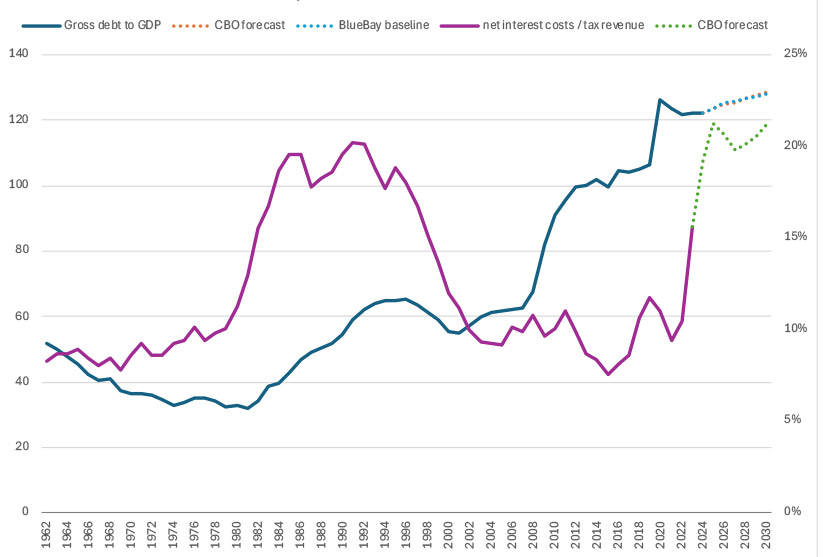

However, the era of cheap debt accumulation has come to an end. Once cheap debt is now becoming expensive as low yielding Covid-era debt is rolled into much higher rates. In Trump’s term in office over the next four years, treasury debt initially issued at yields averaging around 1.6% will have to be refinanced – at levels closer to 4%. This implies that even to keep the fiscal deficit around current levels of -5% to -6% GDP – and thus keep bond supply unchanged at near all-time historic highs – requires at least a 1pp consolidation in the primary deficit. And even then, debt stock continues to amass.

This puts the US budget in a very precarious position. Interest costs are set to absorb more than 20% of tax revenue, a sizeable jump up from the 10% area over the last decade (Chart 3). This is unproductive spending and thus the more of the budget interest costs absorb, the less money is spent towards contributing to GDP growth.

Chart 3: An era of cheap debt accumulation comes to an end

Source: Bloomberg, as at April 2025.

At the same time, structurally we are set to see a reduced government contribution to real GDP growth over the next decade, with mandatory spending on entitlement programs (such as social security and Medicare) to consume a growing share of the budget as more and more baby boomers reach retirement age.

It is worth highlighting that the majority of federal spending does not actually feed into GDP growth. Only spending on services rendered or goods purchased are counted for in G variable of GDP. [GDP = C + I + G + (X – M)]. Transfer payments – to states or individuals, such as social security, unemployment benefits, and Medicare – do not contribute to growth but instead redistribute wealth within the economy. The point here is that fiscal spending is being squeezed on two fronts and thus even while optically a fiscal deficit of around -6% suggests a very stimulative fiscal policy, the reality is the delta on government contribution to real GDP is on the decline.

All data is Bloomberg, unless otherwise stated